A reader asks:

I am following up about your post titled “Planning For Early Retirement“. My wife (59) and I (65) have been retired for 5 years and we follow this strategy: 70/30 allocation primarily invested in index funds + cash reserves equal to 5 years of expenses minus expected cashflows for 5 years from dividends/interest/capital gains distributions (our only income source). The rationale behind this strategy is that there have been only eight 5-year periods with net negative 5-year rolling returns for the total stock market since 1924 i.e. about 8% of the 5-year periods. So, there is a 92% probability that we will not have to sell stocks at a loss. Of course, this may change in the future. However, we are willing to take the risk of ~8% chance of having to take a loss. Do you see any flaws in this strategy?

There are a few things I like about this retirement strategy:

- You’re approaching it through the lens of spending.

- You’re thinking probabilistically.

- You’re melding short-term and long-term planning.

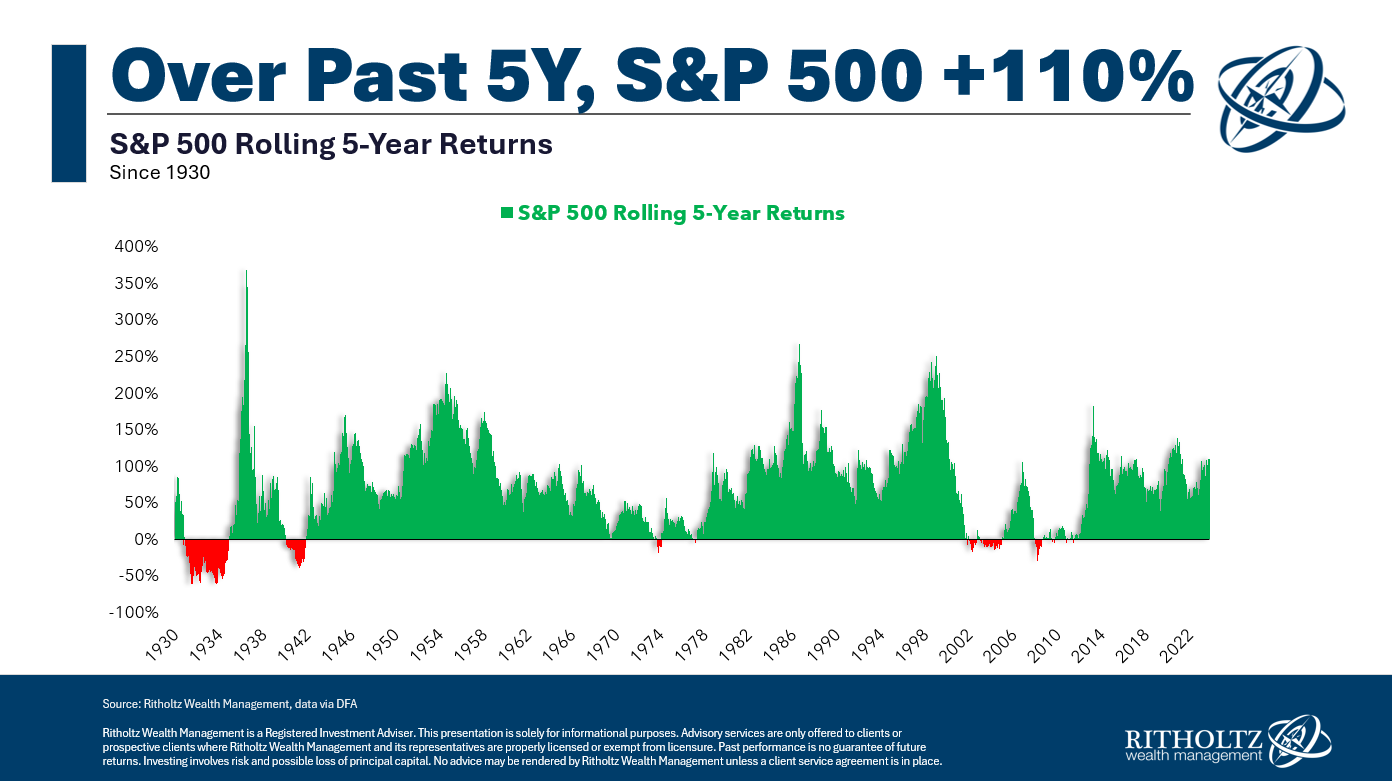

I did have to run the numbers for rolling five-year returns just to make sure (I couldn’t help myself).

Here are rolling 5 year total returns for the S&P 500 going back to 1926:

By my count, returns were positive 88% of the time and negative 12% of all rolling windows. Most of the red on that chart occurred in the 1930s. Since 1950, less than 7% of all rolling 5 year periods saw negative performance. Close enough.

You can’t bank on precise historical probabilities from the past to play out exactly in the future but 5 years is a pretty good cushion.

There are plenty of other factors that go into the asset allocation decision in retirement but thinking about it in terms of liquid reserves can provide a psychological boost for those who are concerned about stock market volatility.

For instance, if you have a 60/40 portfolio and are spending 4% of your portfolio each year, you have 10 year’s worth of current spending in fixed income.

A 70/30 portfolio would be seven-and-a-half years of current spending.

I’m not accounting for inflation in these calculations, and this method assumes you spend down your fixed income during bear markets, which means you’re overweighting stocks and need to rebalance at some point.1

But the whole point here is you want to avoid selling your stocks when they are down.

Sequence of return risk can be a killer if you experience a nasty bear market early in retirement. So I like the line of thinking here.

Is there a right amount in terms of cash reserves? ‘It depends’ always seems like a cop-out answer but it’s true.

Several years ago one of my readers sent me a detailed version of what he called the 4 Year Rule for retirement spending and planning:

1. Five years before retiring start to accumulate a cash reserve (money market funds, CDs) within your retirement plan if possible (to defer taxes on interest). Your goal should be to accumulate four years of living expenses, net of any pension and Social Security income you will receive, by your retirement date.

2. When you retire, your portfolio should consist of your four year cash reserve plus stock mutual funds allocated appropriately. Then, if the stock market is up (at or relatively close to its historical high level) take your withdrawals for living expenses only from your stock mutual funds, and continue to do so as long as the market remains relatively steady or continues to rise. Do not react to short-term minor fluctuations up or down. (As you do this, be sure to keep your allocation percentages more or less at your desired levels by drawing down different stock mutual funds from time to time.) On the other hand, if the market is down significantly from its historical high levels or has been and still is falling fast when you retire, take your withdrawals for living expenses from your four years of living expenses cash reserve.

3. In the event you are taking withdrawals from your four year cash reserve due to being in a severe, long-term falling market, when the market turns up again, continue taking your withdrawals from the cash reserve for an additional 18 months to two years to allow the market to rise significantly (the market almost always rises fast during the first two years of an up market period) before switching back to taking withdrawals from your stock mutual funds. Then return to living off of your stock mutual funds and also start to ratably replenish (over a period of 18 months to two years) your now significantly drawn down cash reserve in order to bring it back up to its required level. Once the cash reserve is fully replenished you are ready for the next severe market downturn when it inevitably occurs.

The stock market won’t always cooperate but I loved the fact that this plan was rules-based and gives a job to each piece of the portfolio.

There is no such thing as an ideal retirement plan because sometimes luck and timing can throw a wrench into the equation — to both the upside and the downside.

How much liquidity you have at any one point should be determined by your risk profile, time horizon and circumstances. There is no perfect answer because the perfect portfolio is only known with the benefit of hindsight.

Successful retirement is a balancing act between the need to beat inflation over the long-run but have enough liquidity to provide for the short-run.

We discussed this question on the latest edition of Ask the Compound:

We emptied the inbox this week covering other questions about getting your CFA designation, the types of bonds you should own in retirement, how pensions fit into a retirement plan, how to spend more money, teaching your kids about money, becoming a landlord, using a HELOC as an emergency fund, how analysts rate stocks and adding international exposure to your portfolio.

Further Reading:

Planning For Early Retirement

1Assuming you would like to keep a relatively steady risk profile.