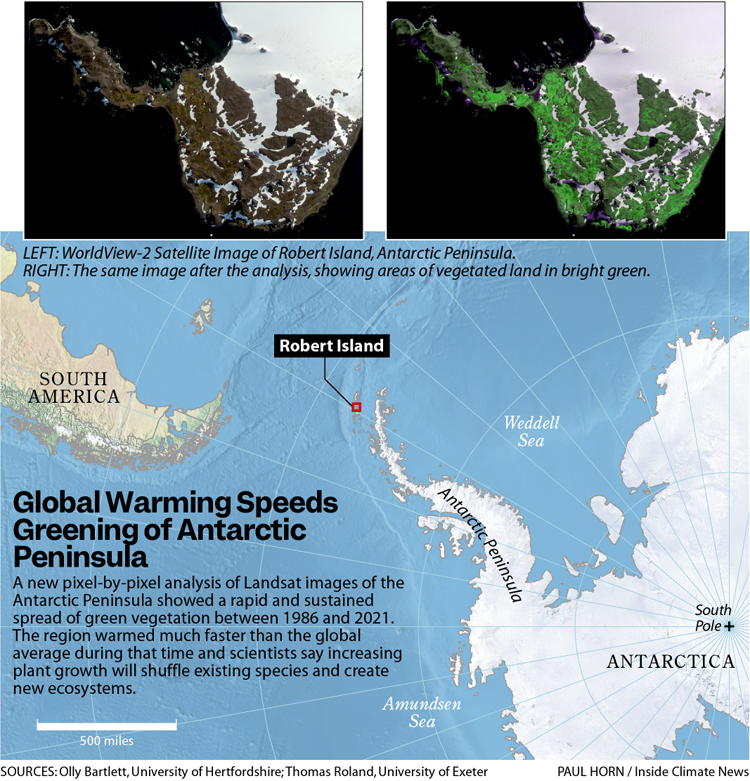

When satellites first started peering down on the craggy, glaciated Antarctic Peninsula about 40 years ago, they saw only a few tiny patches of vegetation covering a total of about 8,000 square feet—less than a football field.

But since then, the Antarctic Peninsula has warmed rapidly, and a new study shows that mosses, along with some lichen, liverworts and associated algae, have colonized more than 4.6 square miles, an area nearly four times the size of New York’s Central Park.

The findings, published Friday in Nature Geoscience, based on a meticulous analysis of Landsat images from 1986 to 2021, show that the greening trend is distinct from natural variability and that it has accelerated by 30 percent since 2016, fast enough to cover nearly 75 football fields per year.

Greening at the opposite end of the planet, in the Arctic, has been widely studied and reported, said co-author Thomas Roland, a paleoecologist with the University of Exeter who collects and analyzes mud samples to study environmental and ecological change. “But the idea,” he said, “that any part of Antarctica could, in any way, be green is something that still really jars a lot of people.”

Credit:

Inside Climate News

Credit:

Inside Climate News

As the planet heats up, “even the coldest regions on Earth that we expect and understand to be white and black with snow, ice, and rock are starting to become greener as the planet responds to climate change,” he said.

The tenfold increase in vegetation cover since 1986 “is not huge in the global scheme of things,” Roland added, but the accelerating rate of change and the potential ecological effects are significant. “That’s the real story here,” he said. “The landscape is going to be altered partially because the existing vegetation is expanding, but it could also be altered in the future with new vegetation coming in.”