Much like with the acorn example above, we had known what to do—we had just not done it to the game’s rather exacting and sometimes obscure standards. The key was to use a glowing gem as a light source, which my brother and I had long understood. The problem was the text parser, which demanded that we “put gem in mouth” to use its light in the tunnels. There was no other place to put the gem, no other way to hold or attach it. (We tried them all.) No other attempts to use the light of this shining crystal, no matter how clear, well-intentioned, or succinctly expressed, would work. You put the gem in your mouth, or you died in the darkness.

Returning from my reveries to the conversation at hand, I caught Ars Senior Editor Lee Hutchinson’s cynical remark that these kinds of puzzles were “the only way to make 2–3 hours of ‘game’ last for months.” This seemed rather shocking, almost offensive. How could one say such a thing about the games that colored my memories of childhood?

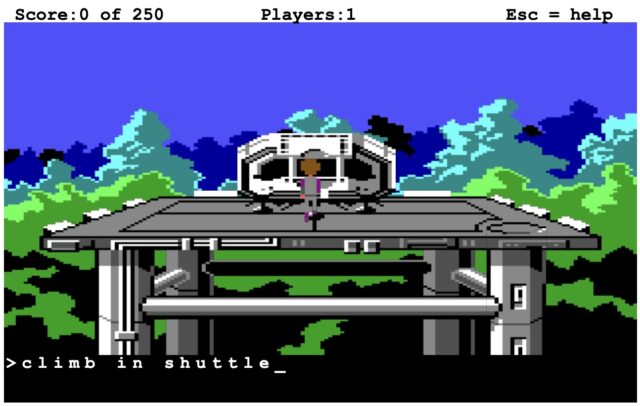

So I decided to replay Space Quest II for the first time in 35 years in an attempt to defend my own past.

Big mistake.

We’re not on Endor anymore, Dorothy.

Play it again, Sam

In my memory, the Space Quest series was filled with sharply written humor, clever puzzles, and enchanting art. But when I fired up the original version of the game, I found that only one of these was true. The art, despite its blockiness and limited colors, remained charming.

As for the gameplay, the puzzles were not so much “clever” as “infuriating,” “obvious,” or (more often) “rather obscure.”

Finding the glowing gem discussed above requires you to swim into one small spot of a multi-screen river, with no indication in advance that anything of importance is in that exact location. Trying to “call” a hunter who has captured you does nothing… until you do it a second time. And the less said about trying to throw a puzzle at a Labian Terror Beast, typing out various word permutations while death bears down upon you, the better.