At the Law and Political Economy (LPE) Conference in Berlin in June 2024 (see Herzog), Stefan Grundmann, the chair of our panel “Polycrises and a substantive approach to private law in Germany”, introduced my contribution by stating: “– and, of course: climate change!”. Why was he right in terming climate change a central issue for LPE debates? Because scholarly debates on climate change law in general and climate change litigation more specifically and the recent LPE debates mutually enrich each other. In this contribution, I outline how and why this is the case. Surprisingly, the interaction of those two fields of study – while evoked frequently – remains underdeveloped.

Climate change litigation in the context of a LPE Symposium

There are at least three reasons for uniting climate change litigation and LPE. First, the founding authors of the LPE movement in their manifesto evoke climate change as one element of the current polycrisis in which LPE accounts have emerged:

“Climate change […] challenges our way of life so fundamentally that it is hard to adequately conceptualize the potential harms in relation to current institutions and intellectual frameworks. […] [T]he costs of climate disruption will fall on those least able to bear them” (Britton‑Purdy et al., at 1788).

Second, climate lawsuits (or at least some of them, as I have argued elsewhere) are intended to challenge the current (fuel‑based) economic model. A leading US climate litigation actor, Our children’s trust, states on its homepage: “The future of 2 billion children is threatened by climate change.” Here, as in other often mutually inspired climate cases, climate change is framed as an inequality problem (among the young and the old, but often also among the rich and the poor, the Global North and the Global South, etc.).

Thirdly, climate change as a global problem perfectly lends itself to legal transplants. There is no “US Climate Change” or “European Climate Change” as there may be a US housing problem distinct from the German housing problem (see on the latter Sammet). Therefore, when it comes to climate change, the inequality problems LPE scholars in the US are decrying resemble those in Europe and Germany.

Against this backdrop, I ask whether for LPE scholars it is worth looking at climate change litigation. The answer is affirmative, which I illustrate by tracing the genealogical development of climate change litigation in the USA and in Europe.

From the USA…

Climate change litigation originated in the USA. Its genealogy points towards two different legal traditions: the first and most well‑known is the inspiration by public interest litigation for civil and labour rights and against the tobacco industry based on constitutional claims. One of the first cases, Juliana v. US, filed in 2015 and ultimately dismissed in 2024, clearly mirrors this reference (see the visual vocabulary in the recent Netflix series on this case). Second, climate change litigation links to the tradition of private enforcement of environmental law, i.e. “the practice of allowing private actors to directly enforce statutes or regulations” (Mance, 2022, at 1497). In the New Deal era, Congress relied heavily on this “decentralized approach to regulatory enforcement” (ibid.). Amidst increasing distrust in the federal government and administration in the 1970s, citizen suits clauses, such as Section 304 of the Clean Air Act, were built into environmental law. From this vantage point, climate change litigation is linked to modern environmental law‑making, i.e. “the last domestic act of the America of the New Deal”, as Purdy, This Land Is Our Land (at 113), put it.

…to Europe…

With the 2015 Urgenda decision in the Netherlands, climate change cases have started to travel the world. In particular, the “civil rights style” cases were transferred to Europe, challenging the poor legislative action in relation to climate change. Then, climate change litigation in Europe took a quite different path to its US counterpart. The Dutch courts refined traditional dogmatic legal concepts such as tort law and human rights in light of climate change, thereby delimiting and concretising legislative room for manoeuvre with regard to climate protection. This trend solidified when in 2021, the Federal Constitutional Court in Germany and in 2024 the European Court of Human Rights (partly) decided in favour of climate protection, providing important guidance for lower instance courts in future climate change decisions. This has led, at least to some extent, to adjusted and more developed climate change legislation in Europe.

…and back

When looking back to the USA today, the wind has changed. As to the tradition of private enforcement, it seems to have failed in climate matters. The shared governance model has recently been criticised as inefficient and even counterproductive in climate change law as private actors increasingly evoke environmental concerns to block climate infrastructure development. However, as to the civil rights tradition, in August 2023, a (district) court for the first time affirmed a violation of constitutional environmental protections with regard to climate change, namely the constitutional guarantee to a clean and healthful environment. In the case Held v. State, Youths successfully challenged the energy policy as anchored in the Montana Energy Policy Act. An appeal is currently pending before the Montana Supreme Court.

Climate cases visualize economic power and the different forms of inequality it creates. As such, they challenge the – essentially lawful – emission of GHG. Thus, they reveal that the (fossil fuel‑based) economy is political both in its origins and in its consequences. It is for this reason that they constitute a perfect case study for LPE accounts. This short genealogical portrait of climate change litigation suggests that the critique of the role of courts as advanced by LPE scholars might need to be adjusted with regard to climate change litigation in Germany and Europe but also in the US in light of current developments. It also urges legal scholars to go out and down, i.e. to focus on numerous jurisdictions around the world as well as on lower instance decisions to grasp the full picture – as climate change litigation scholars have done in an unprecedented way.

A substantive approach to private law

As the question addressed here is twofold, it remains to be answered what we can learn about climate change litigation when adopting a LPE perspective. One major question raised by LPE scholars, on which I will focus here, is whether courts (and legal scholars) apply a substantive approach to private law. By substantive approach, I do not intend the question of private enforcement as a substitute or supplement for regulation as mentioned earlier. Rather, the question is whether and in what ways courts address climate questions in their daily practice and if, by doing so, they touch upon questions of inequality.

On 1 July 2022, the 5th Senate of the Federal Supreme Court in Germany decided upon a provision allowing to build thermal insulation at the outside of buildings in Berlin. § 16a Neighbour Rights Act Berlin states: The owner of a property must tolerate the building over her property of the neighbour’s thermal insulation.

The Federal Supreme Court was doubtful about the constitutionality of this norm with regard to the right to property of the neighbour as enshrined in Article 14 paragraph 1 of the Basic Law – especially because the Berlin state act (unlike equivalent provisions in other Federal States) lacked any possibility for derogation. However, the court’s doubts did not reach the threshold of conviction of unconstitutionality, which would have been necessary for a constitutional review according to Article 100 Basic Law. Why? Because the provision in question serves climate protection (through the saving of energy in the housing sector). The Federal Supreme Court stated:

“[F]rom the legislator’s point of view, § 16a of the Neighbour Rights Act not only concerns the relationship between two property owners whose individual interests are to be reconciled. Rather, it primarily serves climate protection and, thus, a recognized public interest with constitutional status […].”

Moreover, it went on to recognize the specific context of social inequality when it comes to legislative climate matters:

“[I]n the interest of future generations, the legislator is even constitutionally obliged to create incentives for developments in all areas of life that enable the timely transition to climate neutrality.”

Based on this reasoning, the Federal Supreme Court affirmed the provision to be proportionate.

How was such a decision possible? Why did the Federal Supreme Court’s senate in charge of real estate law cases write a climate decision? The answer necessarily refers to the German Federal Constitutional Court’s famous 2021 climate decision quoted by the Federal Supreme Court. In this decision, the Constitutional Court anchored climate protection in the Basic Law (Article 20a). It, thereby, mandated the courts to decide on climate matters. Such enrolment of courts as “climate courts” corresponds with the polycentric nature of climate change pervading the current economic model, and, therefore, touching both upon the private and public law domain. Anecdotally, at least, we can detect a substantive approach to private law in German climate cases.

Is this just a happy story?

Finally, LPE accounts urge us not only to question the role of the judiciary, but also the role of legal scholars and to find out “how we might best reconstruct legal scholarship to address the fundamental challenges of our time” (Britton-Purdy et al., at 1791).

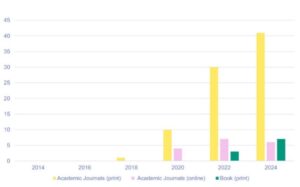

With a look at German contributions on climate change litigation, we can see that legal scholars were late to the party. Figure 1 features scholarly publications on climate litigation in print and online academic journals. It illustrates a significant increase (only) in 2021, the year when, in April, the Federal Constitutional Court issued its above-mentioned climate decision. The same holds true for books, with a little delay due to the heavier publication process. Figure 2 compares non‑academic online contributions to academic print journals and shows that climate litigation has been reported on at least since 2015; however, the significant increase of scholarly contributions happened only after the Constitutional Court’s decision in 2021.

Figure 1 Stabikat search: “Klimaklage/n”

Figure 2 University library search: “Klimaklage/n”

Conclusion

Three claims to conclude. First, courts are increasingly acting as “climate courts”. This holds true for Europe and Germany. The wind might change in a similar way in the US, too, but this development needs still to be consolidated. Second, legal climate change questions anchored in private law reveal the political nature of the current economic model and, therefore, closely relate to LPE debates. Third, and finally, legal scholars in the German discourse seem to have let the courts do the work, before they started to contribute to the debate. This is regrettable, as in addition to a critique of judicial decisions, a proactive and nuanced embedding of questions regarding law and climate change from a scholarly perspective would be desirable and, not least, helpful for the courts in their daily practice of becoming “climate courts”.