This two-part blog looks at the provisions that exist in library laws across European countries concerning the building of collections and what libraries can do with them. It then assesses how far the achievement of these mandated functions is frustrated by a lack of access to e-books.

The first part of this blog provided an introduction to the topic of the interaction between culture laws (library legislation addressing collections) and copyright laws (as expressed in the margin left to rightholders to determine whether and how to allow libraries to licence and lend e-books). This highlighted the connection made between the work of libraries to build and give access to collections and the wider right of access to information. It also underlined the emphasis on the independence of practices here, with the primary guide being to meet the needs of the community and provide the widest possible range of information.

This second part looks at additional expectations and mandates for libraries, and interrogates how restrictions on e-book access risk undermining these. As a reminder, full extracts from laws, with links to original texts, are available here.

Libraries should collect diverse media

While many laws simply do not specify any particular type of media, some explicitly make clear that libraries should be collecting materials in different forms. Flanders calls for a ‘pluriform’ collection, while Bremen, Greece, Trento, Venezia-Giulia and Moldova talk broadly about a variety of media.

Croatia, France, Nord-Rhein Westfalen, Moldova and Slovenia indeed specifically talk about the need to collect and give access to digital materials. The Netherlands does the same, although gives the National Library a specific role in building collections.

The importance of lending

The role of lending in libraries’ ability to fulfil their missions is also set out in a number of laws. Flanders’ law underlines that a duty of libraries is both to offer consultation of a wide offer of books, and:

The lending of materials and files with the lowest possible barriers, in particular for hard-to-reach groups and people with limited incomes.

Estonia’s law sets out:

Loan for in-house use and home lending of items and granting access to public information through the public data communication network are the basic services of public libraries

Similarly, the English, Finnish, Irish, Spanish and Swedish laws also highlight the fundamental nature of lending.

Libraries are also expected to share works between each other, in order to meet needs. The importance of inter-library loan is set out in the roles given to libraries in Czechia, Finland, Poland and Slovenia.

An interesting specific angle is the call in the laws of Moldova and Spain to enable the digitisation of physical materials and then access to these. This makes no reference to being limited only to public domain works.

Building and preserving collections

Another role of libraries – already hinted at earlier – is to build permanent collections and preserve these for the future. The Danish law, for example, calls for libraries to collect ‘an appropriate proportion of published Danish works’, while the Northern Irish law also makes a connection with safeguarding local heritage.

The Estonian law also underlines that collection building is part of the definition of regional and coordinating libraries. The same goes for Lazio, Basilicato, Emilia Romagna, Piedmont and Poland.

While this is again a role more typically associated with national, research or more specialised libraries, some laws stress the place of public libraries in preserving content, especially as concerns materials about the local area. France’s law, similarly, sets out the role of public libraries in preserving works, and so supporting research, as do those of Poland and Lazio amongst others.

The incompatibility of restrictions on e-book access and lending with library laws

As highlighted in the introduction to the first part of this blog, copyright law has not kept up with the practices of libraries in a digital world. What could have been a major turning point – the decision of the Court of Justice of the European Union in VOB vs Stichting Leenrecht – has been undermined by its lack of reference to the possibility of disapplying contract terms or circumventing technological protection measures, as well as the slowness of governments in implementing this aspect of EU law. None have done so fully, with the Netherlands drawing on the judgment to come to a solution which still allows publishers to refuse licenses (a similar situation to that in the United Kingdom).

Crucially, there is also nothing to prevent rightholders themselves from making the most of the powers they have, and simply refusing to licence e-books to libraries. While Geiger and Jütte make a strong case for an access right, it remains the case that libraries either struggle to gain access to works in the first place, or can see this access withdrawn from one day to the next with little if any notice. In short, European copyright law as it stands today very much leaves access to e-books up to the discretion of rightholders.

Yet, across the examples of laws provided above, this discretionary power is not cited as a relevant factor for libraries when determining (digital) collections policies. Indeed, these purely commercial decisions may indeed contrast with the call for libraries to be free of commercial pressures in some laws. While of course libraries need to work within the limits of their budgets, further restrictions based on the discretion of rightholders seem incompatible with true library independence.

In addition it is clear that when a more or less significant share of e-books are unavailable to libraries, it is far harder to meet the conditions set out. Building universal, balanced, responsive, up-to-date collections is far harder when working from a more limited catalogue of works.

With the act of lending itself set out as a core function of libraries too, contract terms and technological protection measures that make it impossible to lend – both to individual users, and between libraries – are also problematic, confounding the goals established by legislators.

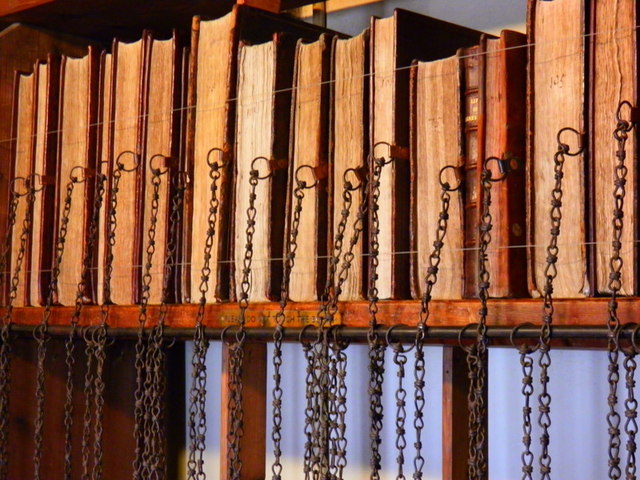

Finally, the model of e-book lending most commonly on offer, with e-books held on publishers’ or other platforms’ servers rather than acquired by libraries, also stands in contrast with those library laws that urge libraries to build collections, as well as to practise preservation. Enough laws are clear that e-books have as much of a place in library collections as physical ones.

In sum, it would appear that an ongoing failure to protect the ability of libraries to acquire, lend and preserve e-books runs directly against the will expressed by legislators when passing library legislation.

Conclusions

This article has set out to explore how library laws from 33 jurisdictions in 17 countries across Europe discuss the building of library collections. It looks in particular to identify common trends between them, notably regarding their integral importance for access to information, and the need to respond to local needs while also offering as wide a range of perspectives as possible. Other shared features include an openness to a variety of media types – with digital explicitly named in some – and then the possibilities to lend and preserve collections.

The article then underlines how restrictions on libraries’ access to e-books, and possibilities subsequently to lend or preserve these, serve to undermine the achievements of these goals, set out by governments and legislators as part of their broader cultural policies.

The impact of this, in addition to the frustration of cultural policy goals, is also wider. Library laws – and in particular provisions on collection building – frequently are designed as part of wider efforts to promote reading, literacy and education (France, Schleswig Holstein, Rheinland-Pfalz, the Netherlands, Sweden). Some go further, noting how this work supports social inclusion (Puglia), democracy (Nord-Rhein Westfalen) and development in general (Estonia, Finland, Rheinland-Pfalz). Insofar as collection building and lending is hindered, so too is work towards these goals.

In short, the ongoing lack of steps to ensure that libraries can access and lend e-books on similar terms to physical ones represents a continuing drag on the achievement of cultural laws and wider public policy goals.