With an order (Cass., ord. no.11413/2024) that suprisingly triggered little attention, at the end of last April the Italian Supreme Court (Corte di Cassazione) proffered yet once more its original approach and reading of the principles inspiring the EU copyright harmonization – and particularly of those developed by the CJEU case law. This time, the casus belli came from a question related to the requirements needed to allow the cumulation of design and copyright protection for works of industrial design and applied art (WAA).

This two-part post analyses the case and its implications. While Part I describes the litigation surrounding the case, Part II moves on to the compatibility of the Italian approach to WAA with the relevant EU copyright rules.

Facts and previous instances

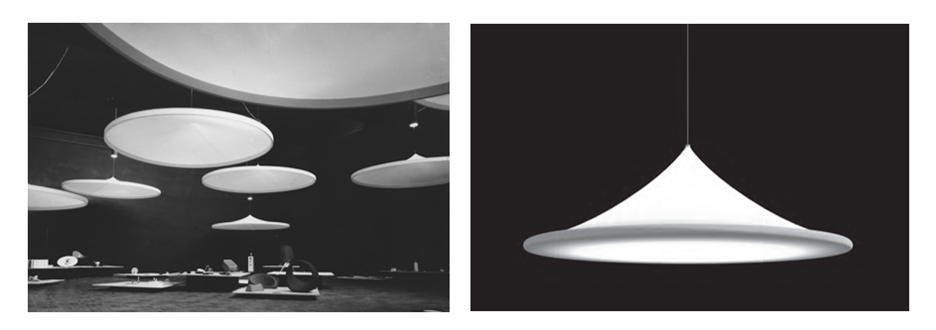

At the heart of the controversy is a lamp (“Lampada 1954”), designed in 2015 by Pietro Maria Castiglioni (nephew of the famous architect Pier Giacomo Castiglioni) and commercialized by a French company, which, according to the daughter and heir of Pier Giacomo, constituted copyright infringement of a similar industrial design lamp realized by Pier Giacomo and Achille Castiglioni for an exhibition featured during the 10th Triennale of Venice in 1954. In the first instance, the Tribunal of Milan ruled in favour of the plaintiff, arguing that the lamp met the requirements for copyright protection and Pietro Maria’s lamp constituted copyright infringement. The first instance court maintained that the lamp embodied a creative contribution and had an artistic value that was independent from the exhibition into which it was embedded, despite its functional integration within the exhibition stand. This was confirmed by the presence of indipendent preliminary sketches featuring the lamp only, and by the fact that the brothers Castiglioni’s lamp played a central role in the exhibition and the public kept on recognizing its aesthetical value in the following decades. The Tribunal also noted that the finding for infringement was almost in re ipsa, since the only difference between the lamp showcased during the Triennale and the “Lampada 1954” was its size (the first represented with 22 cones, having a diameter of 4 metres and a spotlight placed outside; the second having the size of a normal lamp and the lightbulb placed inside the cone).

The Court of Appeal of Milan reversed the decision. Recalling the principles set in a previous decision of the Corte di Cassazione (n.23292/2015, reiterated by Cass. no. 33199/2023 after the Cofemel and Brompton CJEU judgements), it stated that to be granted copyright protection, a WAA should have an “artistic value”, which must be proven by the author and could be desumed from a number of objective elements. They range from recognition of its aesthetic and artistic qualities by the cultural and institutional milieu, exhibition in museums, publication on specialized reviews, the attribution of prices, creation by a renowned artist, or the acquisition of a market value that is clearly higher than the value of its functional elements. The Court maintained that the artistic character of the work lay in the Triennale exhibition set-up and not in the lamp itself, as also testified by the press recognition and awards conferred to the brothers Castiglioni, which consistently referred to the experimental and original nature of the stand. In the opinion of the appelate court, this circumstance confirmed that, in the cultural milieu, the iconic nature of Castiglioni’s work of design was not embodied in the lamp but in its functional integration in the exhibition space – thus copyright protection had to be granted to the set-up and not to its standalone components. In addition, the Court of Appeal ruled out that the lamp was a protectable work of design under art.2(1)(10) of the Italian Copyright Act (law no. 633/1941, l.aut.), as it was not an element of a product intended for mass production. In any case, the court excluded the presence of an infringement by underlining the relevant functional difference between Castiglioni’s lamp and Lampada 1954, laying in the different positioning of the lightbulb.

The heir of Pier Giacomo Castiglioni brought the case in front of the Corte di Cassazione, challenging the Court of Appeal’s reading of art.2(1)(10) l.aut., particularly in light of the most recent CJEU’s decisions on the notion of work and the requirements for copyright protection in the field of design law (Cofemel (2019) and Brompton Bicycle (2020)). She claimed that the precedents of the Italian Supreme Court, followed by the Court of Appeal of Milan, were not in line with the CJEU case law, as they required not only the presence of originality and expression, but also the additional artistic value of the work (and thus the fulfillment of the related additional criteria) in order to grant the cumulation of copyright and design protection.

The order: key points

The Cassazione kicked off by reiterating its criteria to assess the “creative character and artistic value” of a WAA, adding that these elements should be objectively recognizable and evaluated ex ante (Cass. no.22118/2015). It specified that to be protected by copyright, it is not enough that a WAA is creative, original and new, but it should also be possible to distinguish the artistic value of the design from the industrial and functional character of the underlying product, i.e., to evaluate the author’s creative contribution independently from the material support that embodies it (Cass. no. 10516/1994). This allowed the Italian Supreme Court to liaise its reasoning with the acquis communautaire, by confirming that the concept of “work” should be understood as an autonomous concept of EU law, and recalling the notions of “originality” and “expression” and their application to works of design in Brompton Bicycle, which excluded the presence of originality where there is no freedom of artistic choice – that is, where the design is necessary (at least in part) to obtain a technical result or where it is dictated by technical considerations, rules or other constraints.

Instead of applying the principles to the case at stake, however, the Cassazione confirmed the findings of the appellate court without verifying their actual compatibility with the much more expansive approach of the CJEU, as requested by the plaintiff. With a debatable twist in the reasoning, it stated: (a) that the identification of the work represented the outcome of a factual assessment, which fell outside the competence of the Supreme Court; and (b) that in any case the artistic value of the lamp did not play any role in the appellate decision, which radically excluded that the lamp itself constituted an independent work.

The key question raised by the case, thus, remained unsolved: may we still consider the traditional Italian approach to the matter to be in line with the CJEU reading of the notion of work, particularly as applied to WAA in Cofemel and Brompton? This issue shall be explored in Part Two of the post.